We all have a favourite treasure - here is your chance to share your favourite textile-related object or objects with other website visitors. Send us pictures, tell us about it, and explain why you love it so much...

Celia Sutton: Bakuba textiles

Back in the 1980s I was doing my City & Guild textiles course, which needed a project on foreign textiles. Through an exhibition at the then Museum of Mankind I discovered the wonderful raffia (or raphia) textiles from the Bakuba or Kuba peoples in an area which was formerly known as the Belgian Congo.

I was hooked.

The Kuba are a loosely linked group of ‘tribes’ with cultural and linguistic similarities, based in the area of central Zaire between the Kasai and Sankuru rivers. The dominant group is the Bushong (or Bushongo), but many people will have heard of the Shoowa in this context.

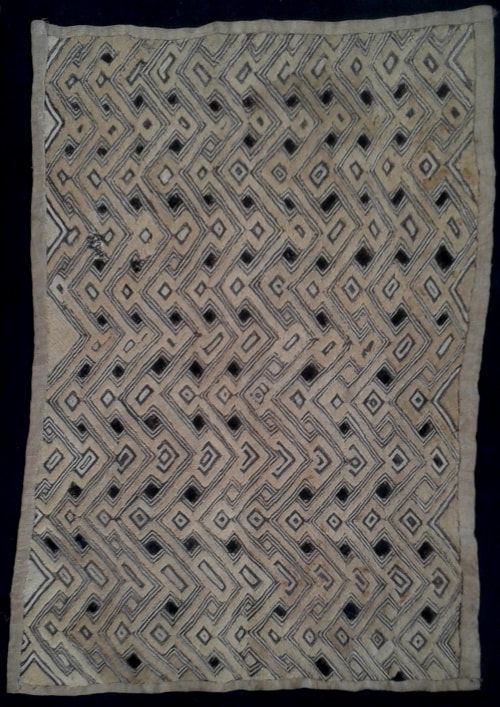

They were quite trendy at the time – people loved the random patterns made by the Shoowa people – but the more regular ones appealed to me. I'm pretty sure the one on the right is Bushong, because of its regularity.

The cloths are on a plain, woven ground, with embroidery added in stitch and in a ‘plush’ technique made by cutting the raffia with a knife, and leading to the name sometimes given them as ‘Kasai velvets’.

They had been written about in the early 20th century by a Belgian traveller called Emil Torday. I read his book at the Sainsbury Research Library, clutching my French dictionary to translate it (I have since bought the book, though my French is no better).

Torday wrote that while the cloth was made from raffia – “the coarse stuff gardeners use”, the finished textile was “as fine as the flimsiest linen” with all the “suppleness of silk”.

I found a variety of articles and books, and also found that the textiles were for sale from specialist dealers. My collection began.

Much of what I knew thirty years ago has drifted out of my brain, although it is all written down in my project work (unfortunately not in computer format). However, there are a few things which stick in my mind.

Back in the 1980s I was doing my City & Guild textiles course, which needed a project on foreign textiles. Through an exhibition at the then Museum of Mankind I discovered the wonderful raffia (or raphia) textiles from the Bakuba or Kuba peoples in an area which was formerly known as the Belgian Congo.

I was hooked.

The Kuba are a loosely linked group of ‘tribes’ with cultural and linguistic similarities, based in the area of central Zaire between the Kasai and Sankuru rivers. The dominant group is the Bushong (or Bushongo), but many people will have heard of the Shoowa in this context.

They were quite trendy at the time – people loved the random patterns made by the Shoowa people – but the more regular ones appealed to me. I'm pretty sure the one on the right is Bushong, because of its regularity.

The cloths are on a plain, woven ground, with embroidery added in stitch and in a ‘plush’ technique made by cutting the raffia with a knife, and leading to the name sometimes given them as ‘Kasai velvets’.

They had been written about in the early 20th century by a Belgian traveller called Emil Torday. I read his book at the Sainsbury Research Library, clutching my French dictionary to translate it (I have since bought the book, though my French is no better).

Torday wrote that while the cloth was made from raffia – “the coarse stuff gardeners use”, the finished textile was “as fine as the flimsiest linen” with all the “suppleness of silk”.

I found a variety of articles and books, and also found that the textiles were for sale from specialist dealers. My collection began.

Much of what I knew thirty years ago has drifted out of my brain, although it is all written down in my project work (unfortunately not in computer format). However, there are a few things which stick in my mind.

- The embroidery on the textiles was done only by women. The men wove the regular, plain raffia fabric for them to decorate. Monni Adams wrote: “The Kuba women use neither sample pattern nor sketches on the cloth; they are working from models in their minds.”

- The pieces were used as decoration, hangings, stool covers, and occasionally as part of clothing but they also had an economic value, being used as tribute to the kings and high-ranking officials, dowries and legal settlement, and as a local currency. When their owner died, the body was wrapped in the cloths as a shroud, and were buried, preventing anyone from building up hereditary wealth.

- Patterns were important, and all had names. One (possibly apocryphal) story is that when a missionary showed a local chief his motorbike, the chief was less interested in the bike than in the patterns made in the earth by its tyres. A pattern derived from that carries the king’s name – a form of immortality.

- Names of patterns include the finger, arm of the chameleon, monkey, hen’s feet fish, snake.

- Raffia was also used for dance skirts, although applique is the more normal decoration for them rather than stitch. It’s thought that applique first arose to hide holes worn in the cloth by the pounding and softening process.