NORWICH SHAWLS...

Norwich Museum Shawls Collection

The Norwich shawls collection includes over 150 complete shawls, and 25 shawl pieces and borders. Norwich was famous for producing dress shawls aimed at the middle and top end of the shawl market from 1800 to 1870, and the city was home to many skilled weavers and dyers who worked for local textile manufacturers throughout the 19th century. Click here to link to the Museum's website

The Norwich shawls collection includes over 150 complete shawls, and 25 shawl pieces and borders. Norwich was famous for producing dress shawls aimed at the middle and top end of the shawl market from 1800 to 1870, and the city was home to many skilled weavers and dyers who worked for local textile manufacturers throughout the 19th century. Click here to link to the Museum's website

THE STORY OF NORWICH SHAWLS...

|

Told by Helen Hoyte, author and textile expert.

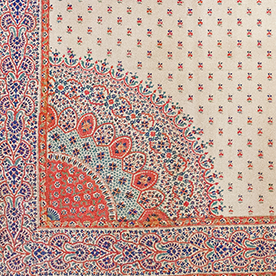

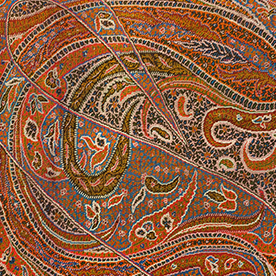

Towards the end of the 18th century, shawls were becoming the ‘must haves’ of the fashionable elite. Most desirable were the magnificent and very expensive cashmere shawls from Kashmir. Worn by princes and nobles, these shawls gave an indication of status and, for European ladies of the 19th century, quality shawls carried the same social significance. The fashion spread rapidly and European manufacturers competed to make shawls which were warm, draped well and could be sold at reasonable prices. In Norwich, silk and worsted cloth, which had made the city famous and prosperous from the 16th century, was ideal for making shawls in imitation of the Indian. To simulate weaving, the coloured patterns in the first shawls were put in with darning stitches. Quickly, weavers replaced the embroiderers; draw-looms had a complex system of cords which raised the heddles for the patterns to be woven into the cloth. The specialist weavers Norwich master weavers employed out-reach workers and as the demand grew, some weavers specialised in weaving shawls. Working in their homes, assisted by draw-boys, the weaver had control of how the design and colours were put into the weave. On receiving a commission from a master, the weaver collected the yarn required and was given a painted design on which a graph showed the crossing points of the warps and the wefts. With the help of the draw-boy, he warped up his loom and started to weave, he called numbers to the draw-boy to pull cords to raise groups of warps; at each change of shed the weaver threw the shuttle across the web and both motifs and colours were built into the weave. The connecting yarns which covered the back of the shawl, had to be cropped (croppings were called ‘shoddy’ to be re-spun if the quality was good); an untrimmed back could weigh over three times the weight of a cropped shawl. When the cloth was cut from the loom, it was a common sight to see a Norwich weaver carrying the beam of his loom with the finished shawl over his shoulder walking to his master’s house in the city, to return the finished weave; on the work being approved, he was paid. At the manufactory (which was usually his residence) the master would have the shawl cleaned, loose ends were trimmed and finished, a fringe was stitched on and the fabric was hot- pressed. The shawl could be marketed locally, or sent to the master’s agent in London to be sold. A receipt for the sale of a ‘Norwich Shawl’ made out by a draper in Gentleman’s Walk in 1846, to a Mrs Fulchar of Bracondale was priced at £7; in today’s value about £770. A success story Norwich weavers were highly skilled craftsmen, with a long reputation for the excellent quality of their work. During the 1830s and 40s they produced shawls with a variety of beautiful designs, whose style was ‘Norwich’ and can be recognised today. It is to the credit of these Norwich weavers of the first half of the 19th century that despite fierce competition form other centres, the political and economic setbacks of the time, Norwich shawls continued to be successful. Not only did Norwich have a high reputation for quality weaving, but also for dyeing. Before William Perkins discovered synthetic dyes in 1856, Norwich was famous for scarlet dyeing. Early in the 18th century, a Norwich chemist, Michael Stark, had perfected a process which dyed silks and worsteds to an identical shade. So successful was his process, that yarns and cloth were sent to Norwich from all over the kingdom to be dyed ‘Norwich Red’. Long shawls were fashionable at the beginning of the 19th century, with deep patterned galleries at each end; early journals encourage ladies to take classes to learn how to display the shawls and themselves! Skirts widened and larger square shawls with borders and grouped designs which encroached into the centres, were popular. Also ‘turnover’ shawls – had plain cream or coloured centres which were surrounded by beautiful patterned borders. Skilful needlework arranged borders for one corner to be folded diagonally to fit into the other border, so making a V shape on the back of the wearer. There is evidence that long shawls were often cut down and made into square shawls and turnovers with expensive borders had new centres to replace worn ones. The Jacquard loom By the middle of the century, the width of skirts had increased and very large shawls were in demand. A Jacquard loom was required to weave the new fashionable, larger, very complex patterns and the Norwich weaver, who had been used to centuries of traditional cloth making, vehemently resisted the use of the Jacquard loom. The overhead construction of punch cards would not fit into his home and the draw-boy was no longer required. But the demands of fashion won and the Norwich weaver, now employed in a factory which could accommodate the height of the loom, no longer had the same control of pattern and colour. Centuries of successful cloth making in Norwich seemed to the Norwich weaver to have been swept away. Objections to the use of the Jacquard loom were resolved and despite increasing competition from other centres – France and Paisley – Norwich continued to make high-quality shawls which found favour with the fashionable elite. At the Great Exhibition in 1851, five Norwich manufacturers displayed their shawls and were highly commended for their work. The 1850s and early 1860s were the most outstanding years for shawl making, with huge four-metre long, all silk, brilliantly coloured, complex patterned shawls for wear with the crinoline. The Great Exhibition

Engravings of the public visiting the Great Exhibition show that most ladies are wearing shawls. Queen Victoria’s passion for wearing magnificent shawls led the fashion. By the 1870s shawl-wearing was in decline. Dress styles changed and the new bustle skirts did not allow shawls to drape well. Women were becoming more active and a mantle with sleeves was much more convenient than a draped shawl over the shoulders. The mass production of Paisley shawls had robbed the shawls of their prestige; it could mean that a lady was in danger of seeing her cook wearing the same style of shawl! So a fashion which had lasted for nearly 100 years was quickly over. Decline By the 1880s Norwich was no longer a competitor in the mechanised manufacture of textiles and an industry which had lasted for 500 years remade itself with shoe making, brewing, chocolate making, engineering, insurance and banking so that the city's prosperity continued. Many shawls have been kept by families as heirlooms; some have been made into dressing gowns, housecoats and jackets. Norfolk Museum Service has a comprehensive collection of shawls from the earliest embroidered shawls to those made during the final flowering of the industry in the 1870s. Helen Hoyte 2016 |

In summer 2018 Helen Hoyte generously gave her time to record a film of some of her immense knowledge and enthusiasm for Norwich shawls.

View three excerpts from that major project here.

|